Plenty of time to digest Day 1; now, finally, here’s Day 2…

The curse of the scriptwriting guru?

John Yorke, the BBC’s Controller of Drama Production and New Talent, is renowned for his engaging and informative lectures on screenwriting. His Series Masterclass at last year’s festival was excellent (see Margit Keerdo’s write-up, here). This year’s session was so compelling, I almost forgot to take notes…

|

| John Yorke. Photo by Jason Arnopp |

We were taken on a tour, from ancient Greece to the present day, via Eugène Scribe’s well-made play (the “first formula”), with the conclusion that the five act structure and the three act structure are fundamentally the same (the latter, a simplification of the former). John cleverly put the structure diagrams of several script gurus’ theories (from the ages) next to each other, to prove that they are all saying the same thing.

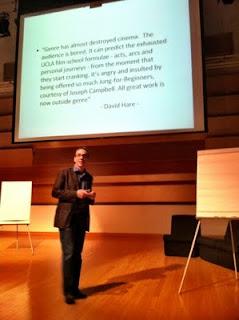

He concluded that while people like David Hare may disparage the “film school”/Syd Field/Robert McKee “formulae” of film structure (see photo), practitioners of every other art form takes pride in the academic study of the history of their art - and that classical drama structure is rooted in history, and in the way that human brains think.

The session ended with the quote:

“First learn to be a craftsman; it won’t keep you from being a genius.” – Delacroix

Launching a new series

This was a festival highlight, with another experienced, successful, know-their-stuff panel.

Jane Featherstone, Kudos’s Creative Director opened by saying it’s about getting the elements right, but it’s also about “alchemy” between those elements, and “luck”. She said: “it all starts with the writer”. Writer, Bill Gallagher said it “starts with the character”. Ashley Pharoah said that, in the case of Wild At Heart, premise came first, then potential for conflict, then character. It’s about having an instinct for conflict that “has legs”. And ensuring that every scene is as entertaining as you can make it.

Toby Whithouse believes you have to “give the audience what they need, rather than what they want”. Audience is broad. You can’t please everybody. It’s not about “producing something facile, in a desperate need to please”. He said he creates massive reams of character bios - digging to create three-dimensional characters.

The panel agreed that the key to a successful series is wit and humour (in terms of take on the world), and that you generally need to “get to the premise more quickly”, in episode one. They referred to the US “premise pilot” and said that In the UK the first series is the equivalent of a US pilot. Series one of Luther lacked “tonal clarity” – rectified for series two. (There’s more on this from Luther writer, Neil Cross, here.)

Ashley Pharoah said that the times he has “come a cropper” are when he has “stepped out of genre”, and that you need to know the rules of what you’re creating: the “world”, and “what it is”. In the telling of the story, you need confidence; you “have to look as if you know what you’re doing!”

Toby Whithouse said that it sounds obvious, but you should show characters “doing their thing” to set them up.

Jane Featherstone thinks that Spooks has kept going for so long because of a “let’s make the next series better” mentality. Total passion, total commitment.

Bill Gallagher wrote thirty-two episodes of Lark Rise to Candleford and absolutely loved the characters, so there was never an episode where he thought, “Oh, God… (not this).” He learned on Casualty that drama is to “create a character (and) throw shit at her.”

Other points made were: it’s about having “an iconic character you love” (for example, Gene Hunt, from Life on Mars) – one that “stands out above the ensemble”. And don’t let characters change and grow too much. An audience comes back to the characters they love. “Things aren’t fundamentally changing greatly.” (Pressing the “reset button” at the end of an episode.)

Thriller – the trojan

“Or: how to smuggle ideas and stories in under the beguiling cloak of genre.”

Some gems of advice here, but my notes are a bit sketchy for this one... (If anyone can fill in the gaps, of who said what, I’d love to hear from you.)

Hugo Blick defined suspense as “knowing what is coming” and mystery as “not knowing what is coming”.

It is manipulative if the writer has an obvious intention.

Thrillers need wit and élan – we can’t get underneath dull characters.

Use the elements of the genre and spin them for your own purposes – will become fresh. Weave in truth. We need to buy into the story emotionally and believe it could happen. Heart and head.

“No tears for the writer, no tears for the viewer.” (The same goes for fun.)

“Sit forward, rip the mask off, don’t be po-faced, have fun!”

Don’t be polite; make the audience uncomfortable. And, in plotting, “don’t show the strings”. In film, “you can really see the strings” and the heart gets pushed out.

Frank Spotnitz said that, as a writer, if you don’t know how it’s going to end, it can be a good thing. He’s been in this position before on The X-Files. How will the audience know how it will end, if you don’t? You’re going to figure it out eventually, because you’ve been setting it up, subconsciously.

It shouldn’t be: “character services plot”. Should be: “only this character can experience this plot.” The perfect goal.

Adaptation

Panel: Paula Milne, Sarah Phelps, Bill Gallagher

Paula Milne likes adaptations for “not having to find the story” – and will do them if she thinks she can “bring something to the table”.

Sarah Phelps asks “why is it a classic?” and “Is it still a classic?” She’ll work on an adaptation if she has a “blood beating passion” for it, and a way to tell the story (the perspective might have shifted). Writing Nancy, in Oliver Twist, she saw Sophie Okonedo’s face. She was criticised for the choice of a black actress in this role, but in classic stories she’s passionate about asking, “who are these characters really?” - and looking at the sweep of history.

Bill Gallagher discussed the idea of adaptation as “translation” and Paula Milne said you can’t be in awe of the book.

Sarah Phelps said she’ll really kick the stories around and interrogate them – and that it’s about telling new audiences “how good these stories really are”.

Burning Questions

Ben Stephenson and John Yorke

Key points:

People still have a hunger for shared experience. (Twitter is about “now”.)

Ben Stephenson said that what moves him is “something someone has a passion for” – he “can’t stand second guessing”. “No great idea ever born out of cynicism.”

The best script note is: “how can it be more itself?” - it's all about tonal clarity.

--------------------------------

If you haven’t been on the Writersroom website recently, it’s an incredibly useful, inspiring and highly addictive resource - and includes scripts by Writers’ Festival panellists, including Paula Milne, Danny Brocklehurst, Toby Whithouse, Jimmy McGovern, Esther Wilson and Alice Nutter.

No comments:

Post a Comment